Most SEOs don’t need to master the ins and outs of technical SEO. But if there’s one foundational topic that everyone in our discipline should understand, it’s crawling and indexing.

Why? URLs would never make their way into search engine results without them, so SEO wouldn’t be a thing. Plus, it’s one of the few instances where YOU get to tell Google what to do. (Don’t tell me that’s not enticing!)

Below, we’ll break down the difference between crawling vs. indexing, how each impacts SEO, and the tools at your disposal to control them.

What’s the difference between crawling and indexing in SEO?

Crawling and indexing are often part of the same conversation, but they’re different processes and Google handles them through different internal mechanisms.

Crawling is how search engines access and read the content of URLs on your domain — if they’re able to do so based on the rules you set.

Whereas indexing is specific to how and whether search engines surface URLs in results for users.

What’s crawling in SEO?

When we talk about crawling in the world of technical SEO, who - or more accurately, what - does the crawling is an important place to start.

Crawling is executed by a bot, script, or program. Each search engine uses its own distinct bot to crawl a site, known as a search engine crawler. In Google’s case, it’s Googlebot.

When crawling the site, it grabs important elements unique to each URL it can access, including:

- Meta robots tag

- Canonical URL

- Hreflang

- SEO title

- Meta description

- Page copy including headings

- Internal links

- External links

We won’t go in-depth into the technical, backend specifics of how search engine crawlers work in this article. Instead, we’ll focus on how crawling impacts your domain’s SEO and what you can do to control it.

What every SEO should know about crawling

When a search-engine bot “crawls” a URL, it’s gathering crucial context to use during indexing and ranking (which, again, are separate processes).

To include a URL in the index (aka the library of URLs surfaced on search engine results pages), the search engine needs access to HTML elements of the page — some of which communicate whether or not to publicly index the page.

If the bot can’t access the HTML, the search engine can’t determine whether the page is available to index or how well it should rank based on the content. The URL won’t show up in search engine results pages in most cases, and if it does, it won’t rank well. (There are some exceptions, which we’ll speak to later in this article.)

For the pages you want to keep Google away from - like order confirmations - that’s good. But for the pages that you want search engine users to find? Not so much.

How do search engines discover URLs to crawl?

There are basically two ways for search engines to discover URLs on your domain.

- They’re submitted in the XML sitemap.

- There are internal pages or external sites linking to the URL.

Without at least one of these, Google can’t discover the URL. It can’t crawl what it doesn’t know about!

If a crawler can access a URL, can it crawl all of the content?

In classic SEO fashion, it depends. If a search engine crawler can access a page, it doesn’t mean it can automatically crawl the content. On many sites, the search engine has to unpack JavaScript to crawl some or even all the important elements.

When crawling these types of sites, Google turns to a third - and, once again - separate process called rendering. It’s a bit out-of-scope for our conversation here since it gets into JavaScript SEO. The important thing to remember is that JavaScript issues sometimes cause snafus with crawling and indexing — and when it happens, it often happens at scale.

What is crawl budget in SEO?

Crawl budget is a term you might hear thrown around, but most sites aren’t big enough to worry about it. Really, only the behemoths of the web — we’re talking thousands upon thousands of URLs, at minimum — run into issues.

In the simplest sense, a site’s crawl budget is the amount of time and resources Google will spend crawling the domain in a given period. (We’ll let them speak to the specifics!)

How does crawling impact SEO?

Here’s the thing about crawl bots. They’re, well… bots. They’re made to do one thing. They don’t have any conception of what to crawl or not crawl. They need directions.

Without guardrails to keep crawlers focused on the right pages, they can aimlessly find their way into the nooks and crannies of your site. Think: subdomains no longer in use, endless variations of search URLs, parameter-based tracking URLs… the list goes on!

By using the tools at your disposal to direct crawlers toward the pages that matter, it focuses resources on pages meant for SEO. That’s a positive because crawlers don’t have to work harder than they need to — or run into as many potential status code errors.

So your site looks good. Plus, there are lots of pages that a crawler simply has no business in!

At the end of this article, we’ll talk about tools at your disposal to control whether or not crawlers can access URLs. For now, here are some basic ground rules when it comes to which URLs to make available or block from crawling.

What you should let search engines crawl

- Homepage

- Product and/or service pages (and variations of them)

- Channel-agnostic landing pages

- Blog articles

- Resources and templates

- Image and script URLs (including JavaScript and CSS)

What you shouldn’t let search engines crawl

- Pages with private information (business or user)

- Checkout pages

- URLs a user has to log in to see

- URLs used for plugins or API functionality (not content)

- Administrative pages that aren’t evergreen (such as terms and conditions that are specific to a one-off promotion or giveaway)

- Excessive duplicate content (when crawl budget is a concern)

- URLs generated by site search functionality

What’s indexing in SEO?

The “index” is the complete library of URLs that a search engine catalogs as potential search results. When talking about SEO indexing, we’re talking about whether or not URLs are a part of that library — aka “indexed”.

Crawling usually precedes indexing because Google wants information as to whether it should index the page, as well as information about what that page is about.

Google uses a different process, powered by an engine named Caffeine, to facilitate indexing. We don’t need to go in-depth into that here. What’s more important is understanding how what you do as an SEO impacts whether or not search engines like Google can surface the pages of your site within its results.

What every SEO should know about indexing

Read it out loud for the people in the back… indexing isn’t a right. Yes, you need to send all the proper signals, so search engines know whether they have permission to index URLs.

But there are two things that a search engine needs to determine for indexing:

- Whether it has permission to index the page

- Whether the page is worth being indexed

Just because a search engine has permission to index something doesn’t mean that it will. Let’s get into some of the nuances.

Will Google index every page I allow it to?

We already gave away the answer on this one.

Indexable URLs should be crawlable AND discoverable too. If a page is indexable, but a search engine never finds it, then it’s not going into the index.

But even if Google finds a URL and crawls it, there’s a chance it might not index the page. Search engines need to make sure that they’re serving users helpful content to create a positive experience.

If the quality of the page or domain is low, Google might decide that the content won’t benefit users. Of course, it’s not always perfect, and low-quality content does make its way into the index.

If you make a page indexable, do it because it’s valuable to users in the first place.

Can a search engine index a URL it can’t crawl?

You wouldn’t think so, since crawling generally precedes indexing. But there’s an important caveat.

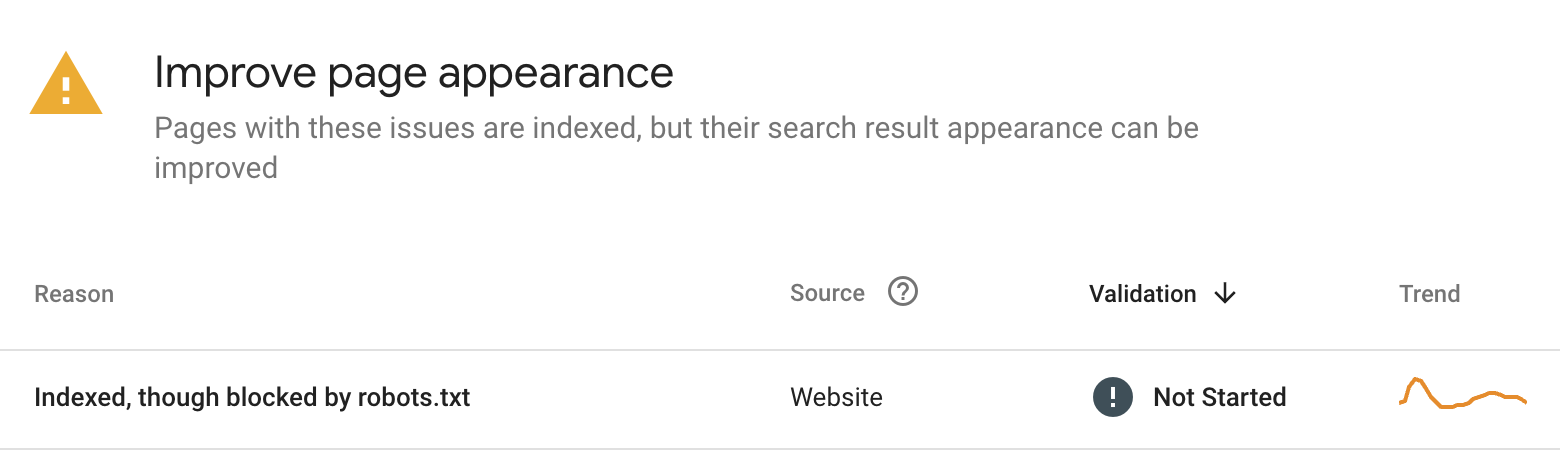

Sometimes, search engines will assume that a page you don’t want crawled has value in the index, based on signals that are out of your control — primarily, backlinks. In this case, you’ll see a result like the one below.

If this happens, don’t worry. You have tools at your disposal to remove URLs from Google quickly.

How does indexing impact SEO?

First, there’s the obvious answer. For a search engine to recommend a URL, it has to be a part of that search engine’s index.

However, it’s not as simple as more URLs in the index inherently means better SEO performance. A lot of how search engines perceive the authority and relevance of a site has to do with the quality of its content.

When a large proportion of the pages that Google can index are relatively low-quality or duplicative, it can perceive that the domain - as a whole - is as well. An abundance of these pages leads to a thin content issue, which in turn drags EVERYTHING down and calls for content pruning.

Controlling what search engines should and shouldn’t index is one of the best ways to protect your domain. If Google can only index and recommend strong content from your site, it’s going to think the site as a whole is up to that standard.

What you should let Google index

- Homepage

- Product and/or service pages (except on sites with enough products to cause potential crawl budget issues)

- Channel-agnostic landing pages

- Blog articles

- Resources and templates

- Author profile pages

- Filter & facet-generated URLs with relevance to user search terms (ex: filters on a category listing page for dresses could create more relevant URLs for queries like “blue dresses,” “maxi dresses,” etc.)

What you shouldn’t let search engines index

- Low-quality or duplicative pages

- Contact form confirmation “thank you” pages

- Non-public information

Which SEO tags and tools control crawling and indexing?

The crawling and indexing tools at an SEO’s disposal are pretty powerful — and they are very much a tool set. Each has its ideal use cases, positives, and drawbacks. To be most effective, an SEO should apply each based on what it does best. (You can’t get a clean slice of bread with a butter knife!)

Robots.txt

The robots.txt is a text file with instructions telling bots/spiders (like Googlebot) what they can and can’t access. It’s implemented at the domain and subdomain level, versus at the page level.

In SEO, it’s a tool to control crawling. It doesn’t directly affect indexing. But like we mentioned, it keeps pages from being indexed in most cases, because Googlebot can’t crawl blocked URLs to assess indexing.

Key terms

- User-agent: The bot or spider the directions are intended for

- Allow: What the user-agent can crawl

- Disallow: What the user-agent is blocked from crawling

What it does well

- This file controls crawling for multiple pages at once — whether site-level, directory- and folder-level, or any set of pages you can define in the syntax.

- It’s helpful for blocking non-relevant, duplicative, or low-quality content (like duplicate facets on eCommerce websites) in large swaths, using a single rule.

- The user-friendly, simple pattern-matching syntax is easy to edit.

- Sites are able to set instructions for specific bots/spiders.

Where it falls short

- The robots.txt only controls crawling — NOT indexation.

- This tool isn’t intended for page-level control, so using it to disallow individual URLs gets messy… quickly.

- The file is publicly accessible, so it shouldn’t include any text with sensitive or confidential information.

- If used incorrectly, it can block large sections of the site in error. (That’s why SEO QA is not to be overlooked!)

Keep in mind...

- Google Search Console’s robots.txt report lets you test whether your file is working as intended. Bing has one too.

- Additionally, Screaming Frog’s tool lets you edit & test rules on the fly.

- Don’t use it as a deindexing tool! Blocking already-indexed URLs will not prompt Google to deindex them.

- You’ll find pages that are still indexed in the “Indexed, though blocked by robots.txt” report.

Meta Robots Tag

Meta Robots is a snippet of code you can add to the <head> HTML or header response of a URL for page-level control of crawling AND indexing. That’s why it includes two directives in the full code snippet. Usually, both are included, but it’s okay to include one or the other.

The first lets search engines know whether or not to index the page (“index” or “noindex”). The second tells crawlers whether or not to follow the links they find and crawl those pages (“follow” or “nofollow”).

Without including this tag, the default assumed state is to both index and follow that page.

Key terms

The four most utilized meta robots tag combinations - in order from most frequently used to least - are:

- “index, follow” - Search engines should index the page, crawl the links, and crawl any linked pages.

- “noindex, nofollow” - Search engines should not index or crawl the page. (Often referred to as a “noindex.”)

- “noindex, follow" - Don’t include the page in the index, but crawl it and temporarily pass PageRank to any linked pages.

- “index, nofollow” - Index the page but don’t crawl or follow any of the links. (This one is pretty uncommon, but sponsored content might be a good use case.)

What it does well

- This tag is unique to the page, so it allows for granular control of individual URLs.

- Since it’s considered a “directive,” search engines will follow your instructions. It’s highly effective at controlling indexation!

- It’s possible to set directives for specific bots/spiders.

Where it falls short

- It's not considered a great tool to save crawl budget, since Google still has to check each page to determine indexing.

- In some technical setups, it might not be easy or possible to update the meta robots tag for certain pages without development help.

Keep in mind...

- The meta robots tag isn’t required, so when it’s missing Google will assume that it’s allowed to crawl and index the URL.

- Search engines cannot follow meta robots directives for URLs that are blocked by robots.txt (since they can’t crawl for the tag).

- With a “noindex, follow” tag, Google will eventually ignore the "follow" command and read it as a “noindex, nofollow” command.

- Google may not see the meta robots tag if it’s served in JavaScript. (If it does, and it conflicts with the tag in the server response HTML, results will vary.)

Canonical Tag

The canonical URL is a snippet of code that’s included in the <head> as well. Rather than providing a directive to search engines, it’s a suggestion.

The tag helps search engines understand the relationship between duplicate or near-duplicate pages - and which of the URLs is the original. But ultimately, the search engine can still crawl each of the pages and choose which to index — i.e. it can and will ignore the suggestion, especially when other signals send conflicting messages.

For example, if a site allows for filtering and faceting on category landing pages, it might have several variations of the same root URL with appended parameters. The canonical URL helps Google understand which is the source page.

The canonical tag is useful for delineating which page takes priority in other common cases too:

- Landing pages with subtle variations for specific audiences

- Content that is republished verbatim on a different site (e.g. syndicated content, however, Google no longer recommends it for this use case.)

- URLs with tracking parameters appended

- URLs for specific configurations of the same product

Key terms

- Canonicalized - The canonical tag of the URL indicates that another URL is the primary version of the page.

- Self-canonicalized - The canonical tag of the URL matches the URL itself, indicating it’s the primary version of the page.

What it does well

- Canonical URLs still pass PageRank, which makes the tag great for consolidating equity across duplicate or near-duplicate pages.

- This method avoids duplicate content issues while giving search engines flexibility to recommend variations where they are helpful to the user.

- The tag is relatively simple to implement with popular CMS plugins.

Where it falls short

- Canonicals are subject to misuse, in which case there’s a good chance Google will ignore them. (It’s for duplicates and very-near-duplicates — don’t stretch it further!)

- Internal and external links to non-canonical variations are the most common reasons Google ignores canonical instructions.

- The canonical tag is not a good solution for crawl budget issues, as Google will periodically crawl canonicalized pages and check each URL for the tag.

Keep in mind...

- Pages without canonical instructions are considered self-canonicals.

- In some one-off instances, Google will ignore the canonical tag if it thinks a canonicalized URL does a better job of meeting user intent.

- Any URL that is included in the canonical tag should reference a self-canonicalized page, otherwise it creates an issue known as a canonical chain.

- Paginated URLs (URLs that reference page 2+ of listing results pages) should self-canonicalize; they are, after all, valid page variations.

- Always use the full-path, case-sensitive URL in the canonical tag.

- Google may not see the canonical tag if it’s served in JavaScript. (If it does, the tag in the JS could conflict with the tag in the server response HTML, so results may vary.)

- Similarly to the meta robots tag, search engines can’t crawl the canonical tag on any URLs blocked by robots.txt.

Remove URL Tool

This GSC tool is only effective for removing URLs from the index temporarily (~6 months). It needs to be used in addition to other deindexing instructions to ensure URLs aren’t indexed again. So it’s a useful tool, but not a standalone tool.

Learn more about how we recommend using GSC’s Remove URL tool.

A note on using tools together

Using these tools together is inefficient at best. At worst, it sends conflicting signals to search engines. While it’s fine in some cases, we recommend avoiding it altogether.

Using the robots.txt with either of the other two tools renders them moot because crawlers can’t get to the tags in the <head>.

Using any meta robots on a canonicalized URL runs the risk of sending mixed messages. In fact, since meta robots is a directive and the canonical is a suggestion, they’re at odds by nature.

It’s worth noting that Google now says it’s okay to use the meta robots and canonical tags together, after years of sending conflicting signals. There are some rare scenarios, where it might actually make sense. We’ll let John Mueller speak to that…

“If external links, for example, are pointing at this page then having both of them there kind of helps us to figure out well, you don’t want this page indexed but you also specified another one… So maybe some of the signals we can just forward along.”

-John Mueller, Google Search Advocate

What’s right for your site?

While these rules and tools apply across sites, the ideal setup for crawling and indexing is specific to your domain. After all, no two domains have the exact same content, business, or goals.

Now that you know the differences between crawling and indexing, how they factor into SEO, and the tools at your disposal to control them, you’re well-equipped to figure out what that means for your site.

As always, we’re here to help connect the dots.